Why Are Carpets Extremely Important to the History of Islamic Art?

The Muslim Rug

The Muslim carpet has long been a luxury article sought by textile museums, rich collectors and wealthy merchants all over the world. The fame of the flying carpet of 'Al'a Al-Din (Aladdin) added some emotional mystery and value to its already exceptional beauty and tangible quality. Information technology is not surprising that carpets still stand for one of the most valuable art items obtained by museums and wealthy families. Furthermore, carpeting is condign one of the essential ingredients of today'south living standard in the mod earth. Modernistic sophisticated manufacturing has made it ane of the cheapest available flooring methods, whilst its comfort and warmth has increased its popularity becoming the largest used flooring organization replacing the ceramics and mosaics. What are the origins of this tradition? What is the Muslim contribution to the history of the carpet manufacture? In the post-obit article, a brief account provides a historical background to the appearance and development of Muslim carpet making; so, lite is shed on its transfer to the West which gradually set a western carpeting tradition.

Rabah Saoud*

Table of contents

1. Historical and cultural background

2. Ottoman and Persian carpets

3. Europe before the carpet

4. The Muslim rug and Europe

v. Faux of the Muslim carpet in Europe

six. Summary and conclusion

seven. References

Note of the editor

A offset version of this commodity was published on www.MuslimHeritage.com in April 2004. The nowadays version was slightly revised and edited, and new illustrations were added.

* * *

i. Historical and cultural background

Muslims regard the carpet with special esteem and admiration. For the traditional Bedouin tribes of Arabia, Persia and Anatolia, the rug was at the centre of their life being used as a tent sheltering them from the sand storms, a floor covering providing nifty comfort for the household, wall curtains protecting privacy, and useful items such every bit blankets, numberless, and saddles. It was indeed a resourceful inspiration to make use of the arable wool produced by their herds.

With Islam, another pregnant value was added to the rug, being a furniture of Paradise mentioned numerous times in the Qur'an. For example in Chapter 88 (Surah), the carpet is counted as one of the riches the believer volition be rewarded in the afterlife.

There is considerable material dealing with the history, nature and character of the Muslim rug. Such textile is published under 3 master themes: the Oriental carpet, the Muslim carpet, or nether regional classification such as the Turkish carpet, or the Farsi carpet and the like. Historic sources take established that the rug tradition is a very old custom practised by early on civilisations. Contempo discoveries (dating from 1949) of a carpeting in the tomb of a Scythian prince in Pazyryk in the Altai Mountains (southern Siberia) date dorsum to the sixth century BCE. This carpet, now in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, is the oldest extant knotted carpet [i]. From a study of its knotting technique, as well equally its decoration, information technology appeared conspicuously that the and so-called "Pazyryk carpet" had a Persian origin [ii]. The next evidence bachelor in the early development of the carpet consists of small 6th-century CE [3] fragments from Turfan (east Turkestan), on the former silk road, which were discovered between 1904 and 1913. It appears articulate from these two evidences that the carpet was start fabricated in the region of what was to become later a substantial role of the Muslim world.

The primeval surviving Muslim carpet, all the same, are fragments found in Al-Fustat (old Cairo). The oldest of these belonged to the 9th century (821 CE), while the remaining were dated to 13th, 14th and 15th centuries [4]. Based on the form of their knots and decorative designs, these fragments were classified into two types. The start group included fragments having a knot like to a later Spanish knot (knotted onto a single warp) and busy with geometrical blueprint similar to Spanish (Andalusian) carpets of the 15th century from Alcaraz [5]. Therefore, these were considered to be the first prototype of the later Spanish design. The other category of fragments incorporated stylised animal presentations and were considered to exist of Anatolian typology from the 14th and 15th centuries, when animal decorative designs were the fashion. The similarity to the Spanish and Anatolian carpets has made some historians think they were only Fatimid imports. Yet, the fame gained by the so-called "Cairene carpets" during the 17th century can only refer to the refinement reached past the Fustat rug tradition.

Rice confirmed this as he argued:

"The fact that similar designs inspired the woodwork of the middle period in Egypt, as well as the known competence of Egyptian weavers in other veins in early times, tends to support the existence of a local carpet industry, and that, if it existed at all, it was probably established as early as the eighth or ninth century." [vi]

Under the Seljuks, the Muslim rug reached a loftier degree of proficiency of technique and high quality of design. Descending from Anatolian origins [vii], the Seljuks brought with them the talent and tradition of carpet making and other arts as they spread their reign to Persia and Baghdad by the 11th century.

Ettinghausen [viii], and many others, considered the Seljuks to be the real originators of the Muslim carpeting. A report of ii specimens of this period, found in museums of Turco-Islamic art in Istanbul and Konya, revealed the characteristics of the Seljuk carpet art. Carpets in the Istanbul Museum belonged to the Ala' al-Din Mosque of Konya, dated back to 13th century when the mosque was first built, and Konya was the capital of the Seljuk of Rum (1081-1302). The carpets of the Konya Museum, however, were originally made for Eshrefoglu Mosque (Eşrefoğlu Camii) at Beyşehir, built in 1298. The carpets incorporated beautiful geometrical designs of stars framed by a band of calligraphy.

2. Ottoman and Western farsi carpets

By the collapse of the Seljuk Caliphate under the invasion of the Mongols, who by 1259 took Persia, Syria and Baghdad, carpet manufacturing seemed to halt for a while. The barbarity of the Mongol assault wiped out whatever artistic production, inevitably affecting the development of the carpeting industry. There are no recorded examples of this period, but historic sources signal that carpet manufacturing recovered afterward a curt catamenia. The famous traveller Ibn Buttuta (1304-1377), for example, talked of the quality of Anatolian carpets, which he found in the hospice to which he was invited [9], and in his travels Marco Polo (1254-1324) praised them as well [x]. Celebrated sources talked of the spread of stylised animal designs during this flow (14th century) (figure 1).

However, the only evidence available is found in some European paintings made by artists of this menstruum, who fabricated contact with some of these carpets. The first painting of Saint Ludovic crowning Robert Angevin fabricated by Simone Martini (circa 1280-1344) in 1317, which is kept at the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, depicted a carpeting with geometrical patterns and eagles under the throne. More paintings of carpets having stylised animal motifs were executed, including The Wedlock of the Virgin of Nicolo of Buonaccorso [xi] (1348-1388), the Madonna and Kid with Saints of Stefano de Giovanni, or that of Anbrogio Lorenzetti Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints.

|

| Figure 1: Anatolian prayer carpet from the pre-15th century, showing stylised animal motifs in symmetrical rectangles. (Source). |

The origins of the depiction of animals have been traced back to the 9th-century Arab republic of egypt, as excavations at Fustat (quondam Cairo) accept revealed the existence of such designs in Cairene carpets. In that location is also a Turkish element in these carpets, every bit shown in these paintings, exhibiting like traditional knotting techniques [12]. Sometime in the 15th century, carpets with brute motifs ceased to exist but and then far no physical explanation has been established. It might be due to the rising of more religious Ottomans who could have prohibited the depiction of such animals, which depiction is Islamically discouraged. Consequently, a return to abstract geometrical forms took place, signalling the starting time of Ottoman art.

The Ottomans gave great impetus to fine art every bit reflected in the quality of various works they produced, peculiarly in architecture and textile. Ottoman carpets gradually became renowned for their adept treatment of constitute motifs, in addition to the sophisticated geometrical and color schemes. Historic testify gathered from European paintings, produced around the second half of the 15th century, shows the eminence and distinction which the Muslim carpeting reached under these leaders.

The virtually famous of these paintings are those of the renowned painters Holbein [13]. These two artists, peculiarly Hans Holbein the Junior, dedicated their paintings to Muslim (Ottoman) carpets that they became named after them the "Holbein carpets". These carpets are characterised by their geometrical design, which consists of a repeated number of squares as the main frame and octagons as the border followed by a band of "S" blueprint and calligraphic designs. The arabesque is used in abundance to fill the squares and the residuum of the expanse.

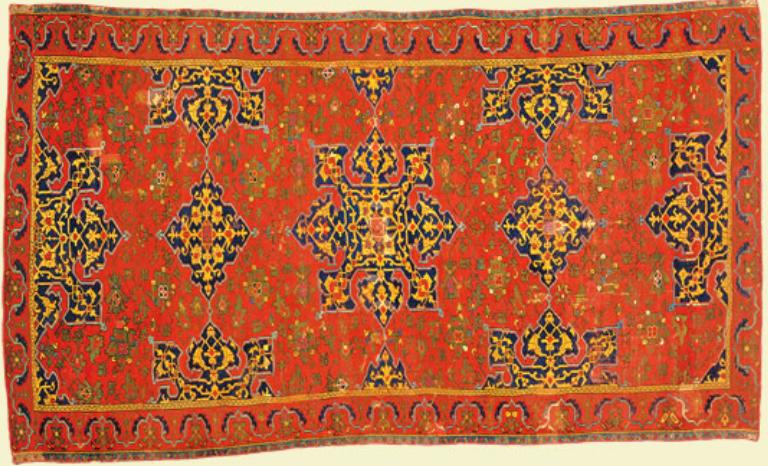

In the 17th century, and under the influence of the Persian carpets, the Ottomans adopted a new way consisting of the inclusion of star medallion and prayer niche patterns, features which extended to most Ushak carpets [14] (figure two). The design and presentation of these elements varied considerably; in some instances the carpet was dominated past the primal medallion, and in others smaller medallions and scrolls were arranged in particular patterns or in a band around the principal theme of the centre. It is worth noting that such designs coincided with the appearance of the Baroque and later on Rococo art styles which appeared in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries respectively. These styles, which were based on arabesque forms organised around geometrical frames and medallions, influenced the evolution of these two art forms.

This is confirmed by Sweetman, 1987 in his statements:

"If we await back from here to 1660 at the fortunes of Islamic and Islamic-inspired art in France and England, nosotros take an overwhelming impression of the importance of decorative arts. The style had a function to play at the Baroque courts of Europe… In England, under later Stuarts, every bit under the Tudors, the brilliance of Islamic textiles and the captivating intricacy of the arabesque found a happy correspondence with existing tastes and also made notable contribution to them." [15]

The Baroque, especially in compages, is highly ornamented with medallions and irregular shapes equally the word 'baroque' ways. Historians admitted its connexion with the Muslims, at least in language format, equally Baroque came from the Portuguese `Barueco' and Italian `Barocco' which is derived from the Standard arabic meaning irregular shaped pearl. The Rococo, withal, used lite and linear rhythms together with natural shapes like shells, corals and ammonites breaking form the formalities of the Baroque style. The Rococo was adult in French republic at a time when it had strong contacts with the east as explained before under the reign of Louis XIV, a time when the Turqueries and Turkish themes were highly appreciated in France.

|

| Figure two: A star-Ushak carpet from west-central Anatolia, dated to the late 16th century. (Source). |

The niche carpets were mainly rugs destined for Muslim prayers, which explains the inclusion of the directional niche (mihrab) in their middle sometimes with a pendulum of light hanging from its arch. This development is a clear sign that the Muslim artist develops his themes from religious as well every bit natural sources. The employ of the mihrab and the lantern in the carpet was highly symbolic, information technology reflected the part of the mosque which locates the direction of the holy Ka'aba besides as translating the Divine meaning of the niche as defined in Chapter 24, Verse 35 of the Qu'ran.

The next development in carpeting chronology is the contribution of Mamluk Egypt (1250-1570). Although in that location are only a few specimens left of the Mamluk carpet, the oldest dates back to only the 15th century, which leaves a considerable period from which no samples are extant. However, there is some evidence that these carpets became renowned for their quality and rich décor [sixteen]. They were mostly characterised by their geometrical designs which included stars, octagons, triangles, rosettes and then on, ofttimes arranged around a big fundamental medallion. Once more, we find arabesque and floral motifs being successfully inserted to fill effectually these shapes giving the design the unity information technology requires. The Mamluk carpets prepare a design tradition that continued to exist influential in almost Egyptian carpets of the 18th and 19th centuries until the nowadays 24-hour interval.

Likewise the Ottoman (Turkish) carpet, no other carpet reached the condition and popularity of the Persian carpet. Every bit mentioned above, the Persians had a long carpet tradition extending dorsum to the Sassanian times. Even so, the earliest surviving evidence of carpeting manufacturing in Muslim Persia were dated to the 15th century mainly through illustrations in miniatures. Carpets were clearly knotted, comprising a rectangular middle dominated past a medallion and a border which sometimes took the form of several bands of various widths [17] (effigy 3).

|

| Effigy 3: Western farsi carpet from Azerbaijan, late 19th century with big primal medallion bordered with "Southward" design band. |

The earliest surviving specimen, however, are but dated to 16th century, the menses of the reign of the Safavids when the production of carpets became a state enterprise, as these rulers adult merchandise relations with Europe and carpeting exporting was at the centre of this trade [18]. Carpets were also considered every bit valuable gifts, exchanged during diplomatic missions to Europe. Under Shah Abbas I (1587-1629), in particular, carpet export and the silk trade became the main sources of income and wealth for the Safavid land. The production took on a wholesale dimension as manufacturers were receiving orders from European consumers. Carpeting making became a professional art, requiring designers to depict patterns first on paper before translating it into woven designs [19].

Persian craftsmen from Tabriz, Kashan, Isfahan and Kerman produced middle dazzling and mesmeric designs ranging from the medallion centred carpets, mihrab carpets (figure 4) and vase carpets to "personalised" carpets bearing the coat of arms of a number of European rulers. Besides these carpets, the Persians excelled in the execution of carpets depicting human being and animal scenes, a new style unparalleled in the Muslim world. By the early 19th century the carpet industry started to decline partly due to celebrated events and conflicts which lost Persia its stability and security in addition to the decline of carpet export equally Europeans established their own manufacturing.

| Features | Turkish | Western farsi |

| Knot class and technique | In the Turkish (or Ghiordes) knot, the yarn is taken twice around two adjacent warp threads and the ends are drawn out between these two threads. | In the Farsi (or Sinneh) Knot, the wool thread forms a single plough about the warp thread. One end comes out over this thread and the other over the next warp thread. |

| Decorative design | Turkish carpets are prominent in the treatment of constitute motifs, using rich colours. | Persian carpets use more human and fauna figures and ofttimes refer to landscape elements, using dominant delicate coaction of red and bluish colours. |

Table 1: Comparison betwixt Turkish and Persian carpets.

The above brief is non exhaustive as other parts of the Muslim world such equally Andalusia, Northward Africa, Afghanistan, and India made also their own contributions to the richness and quality of the Muslim carpets. The concentration, still, has been on these regions for their lasting bear upon on European art.

|

| Figure 4: Cute mihrab Farsi prayer rug from Republic of azerbaijan, belatedly 19th century. |

3. Europe before the carpeting

How did Europe manage earlier the inflow of the Muslim carpet? Celebrated sources bespeak that the earliest floor covering in Europe consisted of rushes. Rushes were scattered over the floor and renewed from time to time [twenty]. This practice continued upwardly to the 2d half of the 15th century. The evidence is found in the illumination of a manuscript at Lambeth Palace (The Dictes and Sayings of the Philosophers) depicting King Edward IV (1461-83) receiving a copy of it from its translator William Caxton [21]. The King was seated in a room strewn with bright green rushes. Hampton Court is said to have had its rushes changed daily on the orders of Fundamental Wolsey [22].

Erasmus (1466-1536) revealed that these rushes were sometimes left likewise long that he condemned their use:

"The doors are, in general, laid with white clay, and are covered with rushes, occasionally renewed, only then imperfectly that the bottom layer is left undisturbed, sometimes for xx years, harbouring expectoration, airsickness, the leakage of dogs and men, ale droppings, scraps of fish, and other abominations not fit to exist mentioned. Whenever the weather changes a vapor is exhaled, which I consider very detrimental to health. I may add that England is not only everywhere surrounded past sea, simply is, in many places, swampy and marshy, intersected past table salt rivers, to say zilch of salt provisions, in which the common people accept so much delight I am confident the island would be much more salubrious if the apply of rushes were abandoned, and if the rooms were congenital in such a way every bit to be exposed to the heaven on two or 3 sides, and all the windows so congenital as to be opened or closed at once, and then completely closed equally not to admit the foul air through chinks; for as it is beneficial to health to admit the air, and then it is equally beneficial at times to exclude it." [23]

In a later stage, rushes were woven into mats and widely used in Europe in this form. A miniature in the Volume of Hoursin the Chateau at Chantilly entitled Tres riches Heures du Duc de Berri depicts the Knuckles (1340-1416) seated at a table nether which the floor is covered with rush matting [24]. The miniature is dated to early 15th century. Another miniature, found in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, shows the Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless (1371-1419), receiving a book in a room displaying blitz-matting floor. Fifty-fifty at times of Queen Elizabeth I, floor blitz-matting was withal used in England. Bear witness from a portrait of William, Earl of Pembroke (d. 1570), shows the persistence of this practice. In fact, blitz matting connected till the reign of Charles I (1625-49) [25].

4. The Muslim carpeting and Europe

The European fascination with Muslim fabric products goes back to the Middle Ages when contacts with the Muslim world, made during the Crusades and trade, resulted in the import of oriental art items, including textiles. Such products were so valued that the Pope Silvester Ii [26] was buried in luxurious Persian silk cloth. The reader may appreciate the significance of this if he learnt that Queen Eleanor, the Spanish Bride of King Edward I, brought to England Andalusian carpets as precious items of her dowry in 1255 [27]. Notwithstanding, the primeval recorded English contact with Muslim textiles was in the 12th century when the grandson of William the Conqueror, who lived in the Abbey of Cluny in that century, gave an Islamic rug to an English church [28].

|

| Figure 5: The painting of Hans Holbein the Younger The Ambassadors (1533). Oil on woods, National Gallery, London. The painting is notable not only because its rug is the one that gave rising to the term "large-pattern Holbein" , but too for its curious rendering, near its bottom heart, of an anamorphic skull, discernible as such only when the painting is viewed at an acute bending. (Source). |

In France, every bit expected, Muslim carpets were known much before and were particularly pop at the fourth dimension of Louis Ix (1215-70) under the name "tapis Sarrasinois", and in 1277 there were trade privileges for this tapis in Paris [29]. A silk cope from a Mamluk sultan of Egypt was inscribed on it ("the learned Sultan", dating from the 14th century) was found in St. Mary's Church building at Danzig. This is not surprising equally the famous geographer and philosopher Al- Idrisi (ca 1096-1166) revealed that woollen carpets were produced in the twelfth century in Chinchilla and Murcia (both now in Spain) and were exported all over the world.

In addition to these historical facts, in that location is another source which provides credible testify enabling u.s. to evaluate the extent of use and the position of the Muslim rug in Europe. The study of paintings fabricated in the tardily medieval period supplied considerable information on how and where these carpets were used and how they were regarded. The earliest occurrences of carpets in European paintings go back to the early on 1300s, starting with the painting of the Italian Simone Martini, Nicolo of Buonaccorso, Stefano de Giovanni, or that of Anbrogio Lorenzetti (meet higher up). In improver to the depiction of stylised animals, in that location was also a Turkish element in these carpets which consisted of using a like knotting technique [30].

"In Renaissance paintings 1 can easily notice a considerable increase in the popularity of Muslim carpets, peculiarly the Turkish and Farsi makes. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries growing trade relations and increasing prosperity of Europe resulted in more importation of Muslim artistic and luxurious goods as European guild (i.e. the educated and wealthy) started to experience a more than comfortable life. Large quantities of rugs, ceramics and other items formed an essential part of this trade, as confirmed by Mills: "By 1500 we reach a time when certain Turkish products were being produced and exported to the W in large number, and pieces evidently Portraits of of import dignitaries from Italy, France, Federal republic of germany, Holland and Belgium illustrated the luxurious usage of these carpets. Examples of these are those portrayed in the work of the German Hans Holbein, the Junior (1497-1543). He chose large patterned carpets, centrally decorated with octagons and framed within a pseudo-Kufic inscription. His painting known as French Ambassadors, for example, depicts two wealthy men standing in front of a table topped with an Ottoman rug [figure 5]. At that place other instances where Ottoman carpets were nowadays in Christian themes i.e. depicting the Virgin Mary in a setting displaying Ottoman textiles [figures 6 &7]. belonging to the aforementioned group are to be establish represented by painters both of Italia and Northern Europe [31]."

Portraits of important dignitaries from Italy, France, Germany, Holland and Kingdom of belgium illustrated the luxurious usage of these carpets. Examples of these are those portrayed in the piece of work of the German language Hans Holbein the Inferior (1497-1543). He chose large patterned carpets, centrally decorated with octagons and framed inside a pseudo-Kufic inscription. His painting known every bit French Ambassadors, for instance, depicts two wealthy men standing in front end of a table topped with an Ottoman carpet (figure 5). There other instances where Ottoman carpets were present in Christian themes; i.e. depicting the Virgin Mary in a setting displaying Ottoman textiles (figures 6 & 7).

|

| Figure 6: The painting The Virgin and Child with the family of Burgomaster Meyer by Hans Holbein the Younger (1528). Oil on wood, Schloss Museum, Darmstadt, Federal republic of germany. (Source). |

In Belgium, similar processes took identify as carpets were subjected to similar privileged treatment. Two examples may suffice hither including the works of Van Eyck (1390-1441) and Hans Memlinc. These two artists, like Holbein, incorporated the Muslim carpeting in their drawings with holy and noble themes. Van Eyck's painting of the Virgin and Child with St. Donatian, St. George and Canon Van der Paele (figure 8), which he painted in 1436 at Bruges, shows Mary seated on a rug with geometrical shapes, essentially circles fatigued around rosettes combined with lozenges and 8 pointed star motifs. His fellow artist Hans Memlinc, in his Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine (1479) and The Virgin Enthroned (figure ix), used those Anatolian patterns very closely resembling the carpet of Eşrefoğlu at Beyşehir [32].

In Italy, the earliest testify of carpets is traced to the end of twelfth century, appearing in increasing number of paintings of this flow, either below the throne of the Madonna (as in the work of Martini to a higher place) on the floor of sacred rites, or hanging from windows of homes on feast days. Past the 15th century, carpets gained more than popularity as they began to appear in documents showing that they were used every bit table carpets (tapedi de tavola), and desk carpets (tapedi da desco). These were both tapedi damaschini, Damascus carpets, and tapedi ciaiarini, Cairo carpets, which invaded the trading markets of Venice [33].

|

| Figure 7: Details of the painting The Virgin and Child. Hither nosotros have medallions made upwards of diamonds and squares. The principal border is a continued "S" blueprint that is more mutual every bit a minor or baby-sit edge. |

In other occasions, Muslim carpets formed stylish diplomatic gifts, specially the stylish Mamluk carpet from Egypt [34]. The portrait of Husband and Wife of Lotto (1480-1556) shows the utilize of the "S" pattern for inner edge combined with a delightful arabesque followed by some other wider border made essentially of vine leaves (figures 12 & 13). The painting of the Venetian Cittore Carpaccio St. Ursula Taking Leave of her Father shows the popularity of rugs actualization on the gunkhole and on balcony of the tower. It is said that these carpets (of the painting) were made by Turkish artists living in Venice in the "Fondaco dei Turchi" which provides another low-cal on how the reproduction of the Muslim/Turkish carpeting, transformed into the so chosen "Venetian Carpaccio", took place [35]. In late 15th century, paintings prove the "Venetian Carpaccio" hanging from the windows and balconies of houses every bit well as thrown on tabular array tops and places where they can be more than visually seen and appreciated. From this fourth dimension, the representation of carpets in paintings spread to Spain, Germany and France [36].

The first arrival of this Ottoman/Turkish carpet to England was recorded in 1518 when Central Wolsey ordered 7 from Venice and another 60 Damascene carpets were dispatched to him in 1520 [37]. Male monarch Henry VIII of England (1509-47) is known to have owned over 400 Muslim carpets [38]. A portrait fabricated for him by Holbein in 1537 shows him continuing on a Turkish rug with its Ushak star [39] while Arabesque is bordering his garment, and other Muslim interlacing patterns appear on the curtains (figure x). In another portrait showing the Rex and Princess Mary (after Queen 1553-eight) seated at a table on which a Turkish carpet is spread (figure 11). Records likewise show that the Earl of Leicester, Robert Dudley, (1532-1588), who lived during the fourth dimension of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), left a total of 46 Turkish carpets and one Persian [40].

Turkish carpets were also caused by Hardwick Hall, formerly Bess of Hardwick which was built past Elizabeth of Shrewsbury in the 1590's. An inventory of the hall'due south volition of 1601 counted 32 carpets [41]. Records besides show that the Hall purchased in 1610 two Turkish carpets for the price of £1315 [42] when they were commencement introduced to England. Carpets were used in brandish places, such as tab coffers, by households with prestige.

|

| Effigy 8: The painting The Madonna with Canon van der Paele by Jan van Eyck (Bruges, 1436). (Source). |

Muslim carpets connected to decorate most of Tudor England's tables, chests, and walls. Information technology was not until the Victorian period (18th century) that they were used on floors. At that place is evidence suggesting that some carpets were made specifically for European customers. The presence of circular shaped carpet that could be used for tables and other cross-shaped carpets that were produced in Egypt can only be suggestive of a European destination [43]. In other carpets, the figure of the crucifixion was inserted in floral motifs, while others carried the European coat of artillery of which some were sent to King Sigismund III (1566-1632) of Poland.

It is quite articulate that the Ottoman carpeting reached an unprecedented position in European high society, as confirmed by Ettinghausen who wrote:

"There is no doubt that carpets exerted a slap-up fascination on would-be buyers and owners, whatever their social position-whether they were Hapsburgs or members of the purple house of Sweden, princes of the church, the nobility, or were simply well-to-do members of the bourgeoisie. Their esteem can be gauged by the fact that they served as the setting for coronations and other of import festive occasions. They became what is at present called a 'status symbol'." [44]

In the 17th century, the carpeting fashion took off strongly as records reveal the existence of many types of carpets; foot carpet, table carpet, cupboard rug and window carpeting [45]. Such overwhelming popularity continues till the nowadays day while the import of carpets from Islamic countries continues stiff despite the fierce competition with Chinese carpets (table 2).

| Country | 1929 | 1967 |

| Austria | – | 355 |

| Belgium | 425 | – |

| Canada | – | 170 |

| Denmark | 600 | 720 |

| French republic | – | seventy |

| Not bad United kingdom | 300 | 100 |

| Kingdom of the netherlands | – | 340 |

| Sweden | 295 | 510 |

| Switzerland | – | 1960 |

| United states | – | 90 |

Table ii: Imports of Oriental (Muslim) carpets. Source: East. Wirth, Der Orientteppich und Europa, Erlangen, 1976, p. 337.

|

| Effigy ix: The painting Madonna Enthroned with Kid and Two Angels (1490-91 past Hans Memling Flemisch (ca. 1440-1494). Oil on woods, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. (Source). |

|

| Figure ten: Portrait of Henry VIII (ca. 1536–37) by Hans Holbein the Younger shows him standing on a Ushaq carpet. Oil and tempera on oak, Fundación Colección, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid. (Source). |

5. Imitation of the Muslim carpeting in Europe

The first imitation of Muslim carpets in Europe was undertaken under the sponsorship of English language patrons [46]. Attempts to innovate the arts and crafts of weaving rug into England were fabricated as early as the times of Elizabeth I. A Victoria and Albert Museum publication reports that a chapter in Hakluyt's Voyages, entitled Certaine directions given… to M. Morgan Hubblethorne (Dier sentinto Persia, 1579), refers to a plan to import Persian carpet makers into England:

"In Persia you shall find carpets of course thrummed wool, the best of the earth, and excellently coloured: those cities and towns you lot must repair to, and yous must use ways to learn all the society of the dyeing of those thrums, which are so dyed as neither rain, wine, nor yet vinegar can stain….If earlier you return you could procure a atypical good workman in the art of Turkish carpet making, yous should bring the art into the Realm and too thereby increment work to your visitor." [4]

Co-ordinate to Sweetman, the earliest carpet made in Europe was that of Verulam carpet which was produced in 1570 at Gorhambury. Other iii carpets were in the drove of Duke of Buccleuch at Boughton bearing the dates of 1584 and 1585. There are other suggestions which point to the being of other copies made in Britain.

|

| Figure 11: Re-create by Remigius van Leemput of Holbein's mural of Henry VIII, Jane Seymour, Henry VII, and Elizabeth of York (1536-37), destroyed in Whitehall Palace fire in 1698. (Source). |

Between the 16th and the 17th centuries, smaller objects such as chair covers, cushion covers and the like, some of which can be establish in Norwich Cathedral, were reproduced in similar knotting patterns as those of the Turkish carpets [48]. In the 17th century, small panels to cover cushions upholstery were produced using Turkish techniques. An oak chair dated in 1649 and covered with such panels is to be institute in Victoria and Albert Museum.

By the 18th century, the carpet industry was established in Britain. A sure French homo with the proper noun Pavisot made carpets, imitating the Savonnerie carpets, at Paddington moving to Fulham by the eye of the 18th century. All the same well-nigh of his production was destined to fulfil orders for piece of furniture covers [49]. Later, in 1751, the Royal Society of Arts promoted the establishment of successful carpeting manufacturing "On the Principle of Turkey Carpets" through subsidies and awards. For example, between 1757 and 1759, the Social club spent £150 as awards for the best Turkish "imitated" carpets. The manufacturers benefiting from these awards were Thomas Moore in Chisewell Street, Moorfield, Thomas Whitty at Axminster, Passavant at Exeter, and William Jesser of Frome [l].

In French republic, a similar approach was followed. In 1604, Male monarch Henry IV promoted a certain Monsieur Fortier and fabricated him "tapissier ordinaire de sa Majeste en Tapiz de Turquie et facon de Levant", to make copies of Turkish and Eastern carpets. A yr after, in 1605, a visitor (the "Savonnerie") was set up by Pierre du Pont to exercise this copying. Later, in 1750 the visitor expanded into England, ii Frenchmen from Savonnerieat Chaillot moved to London and set up up a rug factory showtime in Westminster and later expanded into Paddington and Fulham [51], as outlined to a higher place.

|

| Figure 12: Husband and Wife past Lorenzo Lotto (ca. 1543). Oil on canvas, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. (Source). |

|

| Effigy 13: Close up of carpet in Husband and Wife. Details of the octagonal design on the tapestry. |

Other countries followed adapt. In 1634, Smooth companies were fix in Brody by a certain Hetman Stanislaw Koniecpolski to produce Turkish and eastern styled carpets [52].

6. Summary and conclusion

From the higher up, information technology appears that the European perception of Muslim carpeting has adult over time. What began as a rare luxurious item gifted to the holy and saintly figures, information technology was later possessed but past the rich and ultimately to the institution of local carpet industries. Thus, making it available to a wider public. In this process one tin can distinguish five phases:

- Carpets were outset reserved for holy rituals as seen in the paintings which incorporated them in the delineation of the Virgin, Jesus, the saints and other holy scenes. This took place between the 14th and 15th centuries.

- In the late 15th century the carpet reached the landed gentry condign a status symbol to be displayed from such as windows and balconies (as seen in the "Venetian Capaccio").

- In the 17th century, carpets were a popular decorative particular covering tables, as seen in the Dutch paintings. This period likewise saw the advent of the foot carpet, table carpet, cupboard and window carpets.

- The 18th century marked the start of the rug manufacturing.

- The last ii centuries have seen a wider spread of carpet spreading reaching about houses and offices of the Western world.

This contribution shows the humane dimension of Islamic culture in catering for the comfort and well existence of people through the evolution and spread of carpets. An insignificant particular maybe, if compared to those higher intellectual achievements such as scientific discipline, literature, poetry and the contribution.

vii. References

Ettinghausen, R. (1974), "The Touch of Muslim Decorative Arts and Painting on the Arts of Europe", in The Legacy of Islam, edited by Joseph Schacht and Carles E. Bosworth, 2nd Edition, The Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 292-317.

Gans-Ruedin, E. (1975), Antique Oriental Carpets from the Seventeenth to the Early Twentieth Century, translated from Le tapis de l'Amateur past Richard and Elizabeth Bartlett, Thames and Hudson, London.

Hattstein, M. & Delius, P. eds (2000), Islam: Art and Architecture, Konemann, Köln.

Hunke, Southward.(1969), Shams Al-'arab tasta' 'ala al-Gharb, The Trading Office for Printing Distributing & Publishing, Beirut, 2d edition.

Mills, J. (1975), Carpets in Pictures, Publications Department, National Gallery, London.

Rice, D.T. (1975), Islamic Art, Thames and Hudson, Norwich.

Spuhler, F. (1978), Islamic Carpets and Textiles in the Keir Collection, Faber and Faber, London.

Victoria and Albert Museum (1920), Guide to the Collection of Carpets, HMSO, London.

Wirth, E. (1976), Der Orientteppich und Europa, Heft 37, Gedruckt inder universitatsbuchdruckere Junge & Sohn, Erlangen.

Notes

[1] Gans-Ruedin, Eastward. (1975), Antiquarian Oriental Carpets from the Seventeenth to the Early Twentieth Century, translated from Le tapis de l'Amateur by Richard and Elizabeth Bartlett, Thames and Hudson, London, p. 10.

[two] Ibid, p.12.

[3] Ibid, p.13.

[4] Ibid, p.14.

[five] Spuhler, F. (1978), Islamic Carpets and Textiles in the Keir Drove, Faber and Faber, London, p. 27.

[6] Rice, D.T. (1975), Islamic Art, Thames and Hudson, Norwich, p. 139.

[7] For more details, see FSTC, Architecture Under Seljuk Patronage (1038-1327) on www.MuslimHeritage.com (article published 13 April 2003).

[8] Ettinghausen, R. (1974), "The Impact of Muslim Decorative Arts and Painting on the Arts of Europe", in The Legacy of Islam, edited by J. Schacht and C. E. Bosworth, The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2nd edition, p. 300.

[9] Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa (1325-1354), translated and selected by H. A. R. Gibb, edited by Sir E. Denison Ross and Eileen Power, Robert M. McBride & Company, New York, p. 126.

[x] Sterstevens, A. (1955), Le Livre de Marco Polo, Albin Michel, Paris, p. 73.

[11] Which contains a flooring carpet with octagons depicting eagles, now at the National Gallery of London.

[12] Mills, J. (1975), Carpets in Pictures, Publications Department, National Gallery, London, pp. four-five.

[xiii] Hans Holbein the Elder (1460–1524) father of Hans the Younger, and Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497–1543), amend known of the two, court creative person to King Henry Eight of England. Meet the entries on Hans Holbein in Wikipedia (retrieved 24.04.2010).

[14] Spuhler, F. (1978), Islamic Carpets and Textiles in the Keir Collection, op. cit., p. 47.

[15] Sweetman, 1987, pp. 71-72.

[xvi] Gans-Ruedin, E. (1975), "Antique Oriental Carpets from the Seventeenth to the Early on Twentieth Century", op. cit., p. 21.

[17] Elke Niewohner (2000), "Iran: Safavid and Qajars. Decorative Arts", in Islam: Art and Architecture, edited by M.Hattstein & P. Delius, Konemann, Köln, pp. 520-529.

[18] Blair, S., & Bloom, J. (2000), "Islamic Carpets", Islam: Fine art and Architecture, edited past 1000.Hattstein & P. Delius, Konemann, Köln, Konemann, pp. 530-533.

[nineteen] Ibid, p. 532.

[20] Scott, S.P. (1904), History of the Moorish Empire, The Hippincot Visitor, Philadelphia, vol. ii.

[21] The book was translated from French Les ditz moraulx des philosophes past Guillaume de Tignoville. Apparently it was the first volume to be published in England in 1477.

[22] Victoria and Albert Museum (1920), Guide to the Drove of Carpets, HMSO, London, p. 59.

[23] Cheyney, Eastward.P. (1908), Readings in English History, Ginn and Visitor, New York, pp. 316-317.

[24] Victoria and Albert Museum, op. cit., p. 59.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Reigned 999-1003, also called Gerbert. Born at or near Aurillac, Auvergne, France, about 940-950, of humble parents; he died at Rome 12 May, 1003. Gerbert entered the service of the Church and received his first preparation in the Monastery of Aurillac. He was then taken by a Castilian count to Spain, where he studied at Barcelona and also nether Arabian teachers at Cordova and Seville, giving much attention to mathematics and the natural sciences.

[27] Sweetman (1987), op. cit.

[28] Boase, T.Southward.R. (1953), English Art 1100-1216, p. 170.

[29] Sweetman (1987), op. cit.

[30] Mills, J. (1975), op.cit., pp. 4-v.

[31] Ibid, p. 16.

[32] Gans-Ruedin, E. (1975), op. cit., p. twenty.

[33] Victoria and Albert Museum (1920), op. cit.

[34] Erdmann, K. (1962), Europa und der Orinetteppich, Mainz-Berlin, pp. eleven-17.

[35] Mills, J. (1975), op.cit., p. 17.

[36] Victoria and Albert Museum (1920), op. cit., p. 3.

[37] Beattie, K. (1964), "Uk and the Oriental Rug", in LAC 55, and Mills, J. (1983), "The Coming of the Carpet to the West", in ARTS true cat., the Eastern Carpet in the Western Earth.

[38] King, D. (1983), "The Inventories of the Carpets of King Henry 8", in Hali 5, pp.287-296.

[39] The Ushak star consists of 8 signal indented star motif alternating with lozenge shapes.

[40] Ettinghausen, (1974) , op. cit., p. 301.

[41] Beattie, 1000.H. (1959), "Antique Rugs at Hardwick Hall", in Oriental Art, vol. 5, pp. 52-61.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ettinghausen 1974, op. cit., p. 301.

[44] Ettinghausen (1974) op. cit., p. 301.

[45] Victoria and Albert Museum, op. cit., p. 9.

[46] Sweetman, 1987, op. cit., p. 16.

[47] Quoted in Victoria and Albert Museum, op. cit., p. 62.

[48] Victoria and Albert Museum, op. cit., p. 63.

[49] Ibid, p. 64.

[50] Sweetman 1987, op. cit., note 39, p. 274. Besides see Victoria and Albert Museum, op. cit., p. 64.

[51] Ibid, note 39, p. 40.

[52] Ettinghausen (1974), op. cit., p. 302.

* Dr Rabah Saoud, BA, MPhil, PhD, wrote this article for world wide web.MuslimHeritage.com when he was a researcher at FSTC in Manchester. He is at present an Assistant Professor at the University of Ajman, Ajman, UAE.

Source: https://muslimheritage.com/the-muslim-carpet/

0 Response to "Why Are Carpets Extremely Important to the History of Islamic Art?"

Post a Comment